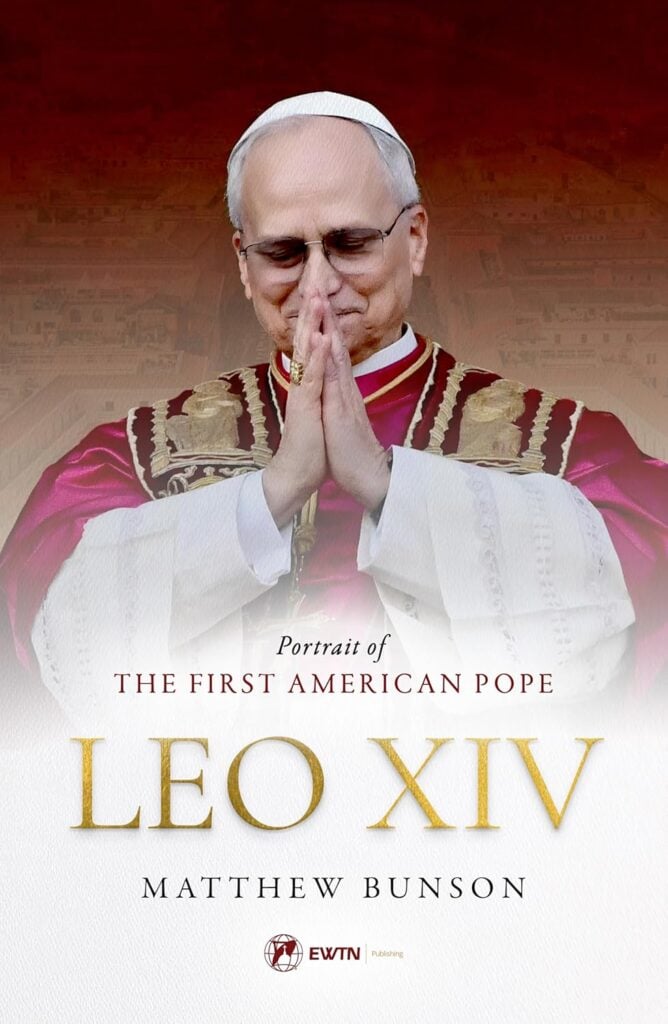

Leo XIV: Portrait of the First American Pope

by matthew bunson

sophia institute, 160 pages, $17.95

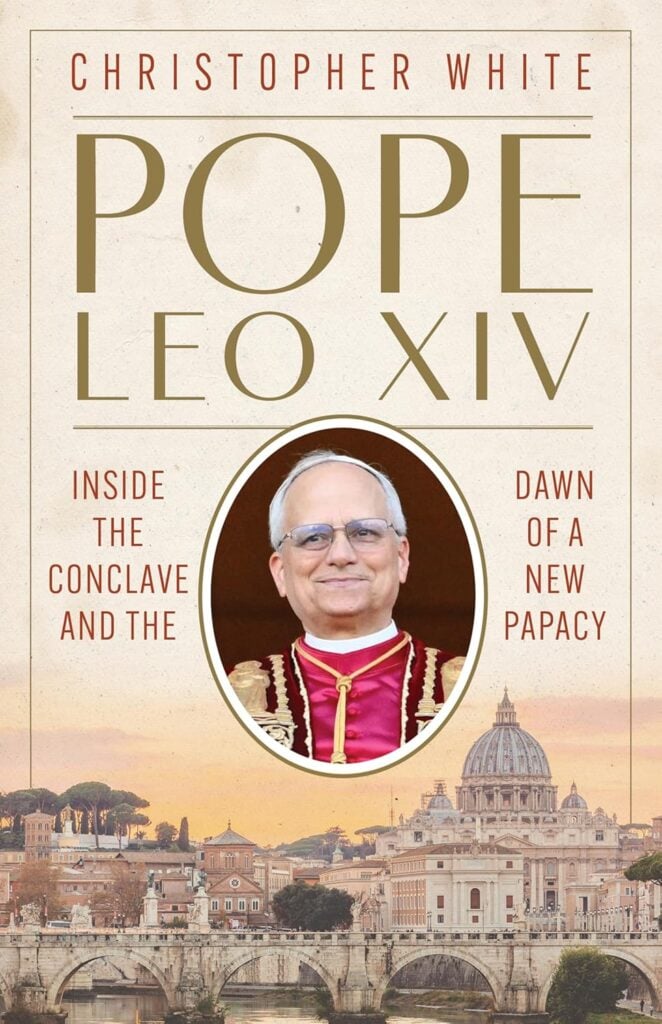

Pope Leo XIV: Inside the Conclave and the Dawn of a New Papacy

by christopher white

loyola, 168 pages, $19.99

Already we have had an array of first-hundred-days analyses of Pope Leo XIV, as though the first American-born pope could be judged like an American president. Yet Robert Prevost of Chicago’s south side is more like an ideal Supreme Court nominee: the able jurist of considerable achievement about whose views not very much is definitively known.

Cardinal Robert Prevost is a man of achievement and wide experience: an American missionary priest in Peru; traveler to dozens of countries as worldwide superior of the Augustinian order for twelve years; bishop of Chiclayo, Peru for a decade; finally, for two years head of one of the most important Vatican departments, that charged with the appointment of bishops.

In the latter roles, he was entirely a creature of Pope Francis. Such figures often rise in the Church hierarchy—men rapidly elevated, made powerful and prominent because of their pontifical patrons. Think of the late cardinals John O’Connor of New York, Jean-Marie Lustiger of Paris, and Carlo Martini of Milan—all creatures of St. John Paul the Great.

After the death of Pope Benedict XVI on the last day of 2022, Francis appeared to feel more free. As long as Benedict was alive, Francis always spoke of his abdication in favorable terms, as an act of courage and humility, opening new paths for the papacy. Less than two months after Benedict was buried, Francis declared his view: The papacy is for life. It was gentlemanly of him to save his honest view for after Benedict was dead.

Francis also seemed then to feel more free in his curial appointments. In 2023, he placed two of his “creatures” at the pinnacle of the Roman Curia—Prevost as prefect of bishops and Victor Manuel Fernandez as prefect of doctrine—before creating them cardinals later that year.

Thus, at conclave 2025, both Prevost and Fernandez were favored sons, comfortable choices for the cardinal electors who desired someone in the line of Francis. The latter, Fernandez, was a nonstarter as the father of the on-again-off-again-by-region fiasco of blessings for same-sex couples, not to mention his eyebrow-raising published writings about kissing and orgasms. Prevost, in contrast, was evidently acceptable to nearly everyone and was on the loggia of St. Peter’s less than twenty-four hours after the first ballot.

Part of his wide appeal was that nothing about him raised eyebrows. Growing up in affluent America, he had admirably chosen to serve as a missionary in Peru; he had gained administrative experience while running his religious order; he had the confidence of Pope Francis but was not a partisan.

Consider that, as prefect of bishops, he managed to get through the marathon synods of 2023 and 2024 and the controversy over same-sex blessings without saying anything notable or attracting any attention to himself. He was billed by the Vatican press as the least American of the Americans, given his missionary service in Peru, but more important was that he was the least Francis-like of the Franciscan creatures.

This history poses a challenge for the two Catholic journalists, one conservative and the other liberal, who have published quick biographies of the new Holy Father.

No comments:

Post a Comment