Reality & Myth regarding Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving as we know it today bears little resemblance to the supposed “first Thanksgiving” in 1621 at Plymouth. The festival with its deep Protestant roots is one shaped by myths, not real history, unlike Catholic feast days and Holy Days, firmly grounded in the events of the lives of Our Lord, Our Lady and the Saints.

In fact, until the 19th century, Thanksgiving was strictly a Puritan event, without any influence on the rest of the American people, commemorated as a harvest day ‘fast and thanksgiving’ ceremony. Further, that “day” was celebrated spottily only in the New England States, in some regions and not others, and never on a fixed date.

Some celebrated it as early as October, others as late as January. And some years in its earliest history, if the harvest was not good or the weather inclement, it was simply ignored. To fix an annual commemoratory feast, well, that would have just been too Catholic for Puritan tastes.

Some celebrated it as early as October, others as late as January. And some years in its earliest history, if the harvest was not good or the weather inclement, it was simply ignored. To fix an annual commemoratory feast, well, that would have just been too Catholic for Puritan tastes.

Now, here is the really surprising data: Until the mid-19th century, the event of a feast shared by the first Puritans with the Wampanoag Indians in October of 1621 was completely unknown.

It was a New Hampshire Episcopalian woman, Sarah Hale, editor of the popular Godey’s Lady’s Magazine, who came across a Puritain diary revealing the existence of the gathering of Pilgrims and Indians in 1621. She thought to take advantage of that forgotten commemoration in order to shape it into an “American” feast day.

In 1845, she launched her “crusade” to make a Thanksgiving national feast, stumping relentlessly for the festival in her popular and influential magazine and barnstorming politicians, preachers and presidents. In Godey’s pages, the Pilgrims with their buckled hats, the feathered-banded Indians, and the turkey and pumpkin made their first appearance, along with sentimental short stories trumpeting New England Protestant values of simplicity, economy and patriotism.

Sarah Hale was finally successful when Lincoln established Thanksgiving as a national holiday in 1863 as one means to help mend the broken North and South relationship. It would be a national holiday of food and family values whose central point would be a meal and not religious covenant.

Sarah Hale was finally successful when Lincoln established Thanksgiving as a national holiday in 1863 as one means to help mend the broken North and South relationship. It would be a national holiday of food and family values whose central point would be a meal and not religious covenant.

Instead of being turned toward heaven, in fact, the day’s focus became home, family and nation, that is, America in its “providential role” as republic builder, America as the melting pot that took in all peoples and integrated them into the democratic ideal. Hale envisioned Thanksgiving as one way to bring Americans together much the same way that Protestant women later promoted the Pledge of Allegiance to foster patriotism and national unity, which is another story.

Lincoln also established its official date as the final Thursday in November. Needless to say, the South was loathe to adopt any law coming from the hated Lincoln, and it would take many years for the holiday to achieve its goal or begin to resemble the distinctly American secular holiday we know today.

Immigrant Catholics, who still observed the Catholic feasts and holydays, were also reluctant to embrace this strictly secular feast, which they considered Protestant. It was Cardinal of Baltimore James Gibbons (1834-1921), the great champion of Americanism and religious liberty, who was the first Prelate to make public efforts to integrate Catholics into the Protestant festival.

In 1888, he published in his archdiocesan paper a circular where he called on his priests to recite this ecumenical prayer at the close of Mass on Thanksgiving Day directing its observance: “The faithful of the Archdiocese having in common with our fellow citizens, deep cause for gratitude to the Giver of every good and perfect gift, will, we feel confident, be equally desirous of evincing their spirit of thanksgiving.”

This won him points with the New York Herald, who praised him highly for the act, and with President Cleveland. But, if the Cardinal’s gesture won him admiration from Protestant quarters, it met with strong protest from many fellow Prelates, especially those in the South. Bishop Benjamin J. Keiley of Savannah (GA), complained publicly that Gibbons had “out-heroded Herod” by inducing Catholics to recognize “the damnably Puritanical substitute for Christmas.” (1)

This won him points with the New York Herald, who praised him highly for the act, and with President Cleveland. But, if the Cardinal’s gesture won him admiration from Protestant quarters, it met with strong protest from many fellow Prelates, especially those in the South. Bishop Benjamin J. Keiley of Savannah (GA), complained publicly that Gibbons had “out-heroded Herod” by inducing Catholics to recognize “the damnably Puritanical substitute for Christmas.” (1)

It would take many years – after the more generalized secularization and commercialization of Thanksgiving that occurred in the post World War I era – before Catholics as a body would accept the secular holiday. The 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia makes this revealing remark: “Catholic recognition of the day by special religious features has only been of comparatively recent date and not as yet of official general custom.”

The Pilgrims’ fast and thanksgiving day

So, what is the real history of the real “first thanksgiving”? Summarizing, it could hardly be more different from the story of Pilgrims and Indians meeting in ecumenical joy at a feast of fellowship, the fable we know today.

The Plymouth Pilgrims followed their English counterparts who despised the many Catholic holydays and feast days. But they went a step further, thinking the Church of England beyond reform because it was still too Roman. According to them, all these Popish inventions involved too much ceremony, too much celebration and were unsupported by Scriptures.

So, the Puritans reduced the holydays and feast days to one: the Sabbath. These first Pilgrims, who landed on American soil, hated holydays and festivity so much that they even abolished Christmas and Easter.

A custom developed among the Pilgrims, however, that of declaring special days of thanksgiving in response to God’s providence. The day of thanksgiving was preceded by a day of fast. The majority of the second day was spent in their temple houses praying, singing and Scripture reading. Feasting played little and often no role in the early Pilgrim thanksgivings.

The Massachusetts Pilgrims of Plymouth did not view the 1621 feast celebrated between the Wampanoag Indians and the Pilgrims as a “first Thanksgiving;” they certainly had no intention of inaugurating an annual holiday. This “fast and thanksgiving day” that Governor Bradford called to commemorate the year’s good harvest was, like all others, to note the passing of one providential moment, the good harvest of that particular autumn.

The Massachusetts Pilgrims of Plymouth did not view the 1621 feast celebrated between the Wampanoag Indians and the Pilgrims as a “first Thanksgiving;” they certainly had no intention of inaugurating an annual holiday. This “fast and thanksgiving day” that Governor Bradford called to commemorate the year’s good harvest was, like all others, to note the passing of one providential moment, the good harvest of that particular autumn.

When George Washington issued an ad hoc proclamation of a national day of thanksgiving, he did so in the Calvinist spirit. The Continental Congress proclaimed November 1, 1777, as a nationwide day for fasting, prayer and thanksgiving for the English defeat at Saratoga that ensured a French alliance with the newly born Republic. John Adams and James Madison issued similar proclamations for other “providential” events.

The Thanksgiving we know today was invented and reinvented several times, but has little to do in fact with those original Pilgrims, Indians or turkey dinner.

In my opinion, knowing the history of Thanksgiving strengthens the argument for celebrating the Catholic thanksgivings of St. Augustine, Florida and El Paso, Texas. It makes more sense for Catholics to honor the first Masses said on Catholic soil than the original Protestant fast and thanksgiving day that commemorated the Pilgrim’s “covenant with the Lord.”

Still we can commemorate it on the fourth Thursday of November, or any other day, joining together with family and friends to thank God for our Catholic past and ask him to take up again the original plan for our Nation that it may rightly celebrate the Reign of Christ and Our Lady in all its festivals and actions.

In fact, until the 19th century, Thanksgiving was strictly a Puritan event, without any influence on the rest of the American people, commemorated as a harvest day ‘fast and thanksgiving’ ceremony. Further, that “day” was celebrated spottily only in the New England States, in some regions and not others, and never on a fixed date.

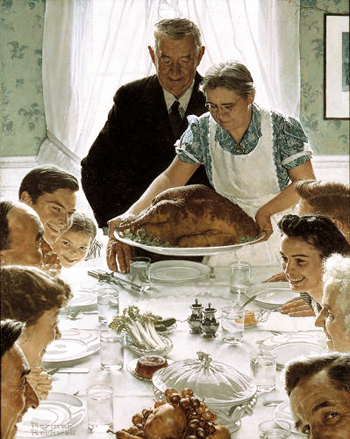

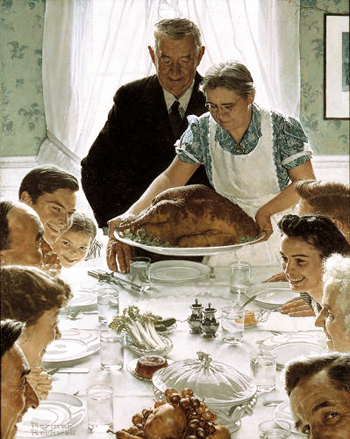

This idyllic first Thanksgiving painted in the early 20th century is a fable, not reality

Now, here is the really surprising data: Until the mid-19th century, the event of a feast shared by the first Puritans with the Wampanoag Indians in October of 1621 was completely unknown.

It was a New Hampshire Episcopalian woman, Sarah Hale, editor of the popular Godey’s Lady’s Magazine, who came across a Puritain diary revealing the existence of the gathering of Pilgrims and Indians in 1621. She thought to take advantage of that forgotten commemoration in order to shape it into an “American” feast day.

In 1845, she launched her “crusade” to make a Thanksgiving national feast, stumping relentlessly for the festival in her popular and influential magazine and barnstorming politicians, preachers and presidents. In Godey’s pages, the Pilgrims with their buckled hats, the feathered-banded Indians, and the turkey and pumpkin made their first appearance, along with sentimental short stories trumpeting New England Protestant values of simplicity, economy and patriotism.

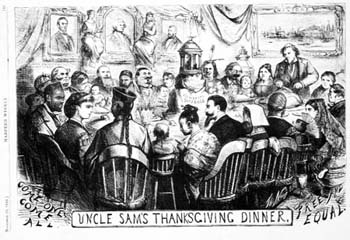

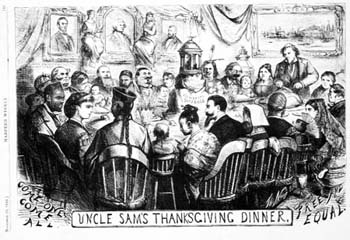

A Victorian age depiction of the Thanksgiving devised by Sarah Hale

Instead of being turned toward heaven, in fact, the day’s focus became home, family and nation, that is, America in its “providential role” as republic builder, America as the melting pot that took in all peoples and integrated them into the democratic ideal. Hale envisioned Thanksgiving as one way to bring Americans together much the same way that Protestant women later promoted the Pledge of Allegiance to foster patriotism and national unity, which is another story.

Lincoln also established its official date as the final Thursday in November. Needless to say, the South was loathe to adopt any law coming from the hated Lincoln, and it would take many years for the holiday to achieve its goal or begin to resemble the distinctly American secular holiday we know today.

Immigrant Catholics, who still observed the Catholic feasts and holydays, were also reluctant to embrace this strictly secular feast, which they considered Protestant. It was Cardinal of Baltimore James Gibbons (1834-1921), the great champion of Americanism and religious liberty, who was the first Prelate to make public efforts to integrate Catholics into the Protestant festival.

In 1888, he published in his archdiocesan paper a circular where he called on his priests to recite this ecumenical prayer at the close of Mass on Thanksgiving Day directing its observance: “The faithful of the Archdiocese having in common with our fellow citizens, deep cause for gratitude to the Giver of every good and perfect gift, will, we feel confident, be equally desirous of evincing their spirit of thanksgiving.”

A 1869 illustration by Thomas Nast displays the new ideal: a table around which all Americans sit

It would take many years – after the more generalized secularization and commercialization of Thanksgiving that occurred in the post World War I era – before Catholics as a body would accept the secular holiday. The 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia makes this revealing remark: “Catholic recognition of the day by special religious features has only been of comparatively recent date and not as yet of official general custom.”

The Pilgrims’ fast and thanksgiving day

So, what is the real history of the real “first thanksgiving”? Summarizing, it could hardly be more different from the story of Pilgrims and Indians meeting in ecumenical joy at a feast of fellowship, the fable we know today.

The Plymouth Pilgrims followed their English counterparts who despised the many Catholic holydays and feast days. But they went a step further, thinking the Church of England beyond reform because it was still too Roman. According to them, all these Popish inventions involved too much ceremony, too much celebration and were unsupported by Scriptures.

So, the Puritans reduced the holydays and feast days to one: the Sabbath. These first Pilgrims, who landed on American soil, hated holydays and festivity so much that they even abolished Christmas and Easter.

A custom developed among the Pilgrims, however, that of declaring special days of thanksgiving in response to God’s providence. The day of thanksgiving was preceded by a day of fast. The majority of the second day was spent in their temple houses praying, singing and Scripture reading. Feasting played little and often no role in the early Pilgrim thanksgivings.

Norman Rockwell portrays the familiar Thanksgiving accepted by all Americans by the mid-20th century

When George Washington issued an ad hoc proclamation of a national day of thanksgiving, he did so in the Calvinist spirit. The Continental Congress proclaimed November 1, 1777, as a nationwide day for fasting, prayer and thanksgiving for the English defeat at Saratoga that ensured a French alliance with the newly born Republic. John Adams and James Madison issued similar proclamations for other “providential” events.

The Thanksgiving we know today was invented and reinvented several times, but has little to do in fact with those original Pilgrims, Indians or turkey dinner.

In my opinion, knowing the history of Thanksgiving strengthens the argument for celebrating the Catholic thanksgivings of St. Augustine, Florida and El Paso, Texas. It makes more sense for Catholics to honor the first Masses said on Catholic soil than the original Protestant fast and thanksgiving day that commemorated the Pilgrim’s “covenant with the Lord.”

Still we can commemorate it on the fourth Thursday of November, or any other day, joining together with family and friends to thank God for our Catholic past and ask him to take up again the original plan for our Nation that it may rightly celebrate the Reign of Christ and Our Lady in all its festivals and actions.

- John Tracy Elliot, The Life of James Cardinal Gibbons, Milwaukee: Bruce Publishing Company, vol. II, pp. 5-6.

No comments:

Post a Comment